Directly on the heels of his sublime five Sundays of

What Little Johnny Wanted, Gus Mager created another fascinating, short-lived Sunday comic strip,

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar, which only lasted for six weeks. After his brief foray into the violent fantasies of young Johnny, Mager shifted his focus onto western culture itself, presenting the disastrous adventures of a full grown, fussy American salesman attempting to peddle the wondrous goods of his civilized world to the African inhabitants of a less technological society.

When I read Mager's

Pete the Pedlar, I see a comic strip version of Randy Newman's 1972 song,

Sail Away. Each

Pete Sunday begins with him arriving on an African shore, selling to the natives. In Newman's song, regarded among many as his best and a landmark of American culture, a slave trader arrives on an African shore and woos the natives:

In America you'll get food to eat

Won't have to run through the jungle

And scuff up your feet

You'll just sing about Jesus and drink wine all day

It's great to be an American

Ain't no lions or tigers-ain't no mamba snake

Just the sweet watermelon and the buckwheat cake

Ev'rybody is as happy as a man can be

Climb aboard, little wog-sail away with me

- Randy Newman (Sail Away)

Of course, everything the slave trader is saying to the natives is a lie. These lyrics are bathed in a beautiful, soaring score that belies the savage truth. Similarly, Mager's

Pete appears to be a funny little screwball comic. Could Mager have been wryly commenting on the lies of consumerism in

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar? Note the name of Pete's company: Joblot and Bunkum (for those not in the know, "bunk" is slang for false information.) Even though the machinery and machine-made goods Pete sells are functional, the ritual of the sales pitch always devolves into chaos for him and his potential customers. A hippo eats a record player and chases Pete, with a song streaming from his open mouth -- this, to me, seems to inhabit a more poetic and beautifully surreal space than the pranks of the smirking Katzenjammer Kids, or the mischief of the eternally repentant Buster Brown.

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar ran from November 11 to December 16 in 1906. In the first episode, Pete has rowed ashore from his big, two-masted ship, visible on the horizon. He is greeted by a grinning giraffe, a leering hippo, a curious ostrich, and jungle natives who are oblivious to both the process of a proper sales transaction and the intended use of the products Pete peddles. By the end of the first adventure, the drooling hippo (the spirit animal of the Consumer?) attempts to consume not Pete's wares, but the "pedlar" himself! Here's a paper scan from my collection:

![]() |

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar by Gus Mager, November 11, 1906

(Collection of Paul Tumey) |

Mager has given us here a comic strip that appears to be like the usual half-page Sunday comedies of the period, but one which is actually more sophisticated in both content and execution. Here's the same page in color, from the archives of Ohio State University's

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum:

![]() |

| (Collection Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum) |

I love the native in the background of panel 3, who has helped himself to Pete's boatload of paintings -- he appears to be quite the art lover!

It's also worth noting that, with

Pete the Pedlar, Mager had designed yet another strip that allowed him to draw his beloved jungle animals, particularly hippos and monkeys. In an issue of

Cartoons, William P. Langreich wrote of Mager:

"Gus Mayer (sic), the author of the famous "Monk" series, always did like to draw animals. Hippos and monkeys were his favorites..." Given this, it's no surprise that the second Pete adventure features a howling hippo, with an operatic ostrich thrown in, for good measure.

![]() |

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar by Gus Mager, November 18, 1906

(Collection of Paul Tumey) |

I love the look of surprise on the hippo's face when the music from the swallowed record player erupts from his mouth. By the last panel, he has begun to embrace the new development and lifts his head in song.

It goes without saying that the depiction of the tribal king in the strip above is less than flattering -- but then so is the caricature of the wimpy peddler. I don't actually see anything particularly racist in Mager's natives other than the use of the formulaic big-lipped, bug-eyed way of cartooning a black man that was popular for decades in American newspaper comics. In fact, the so-called civilized white-skinned Pete appears to be pretty idiotic in comparison to the natives of these comics. In the strip above, the King, startled by a jack-in-the-box toy exercises his royal power on Pete with a lordly comment: "You WILL play tricks on me!"

That same week, Mager drew the topper vignette for

Buster Brown, and indulged his love of hippos and monkeys. These Mager toppers have nothing to do with the content of Richard F. Outcault's

Buster Brown comic which ran below them.

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - Nov. 18, 1906 |

In the third episode, Pete attempts to sell the natives a pre-fabricated house and discovers that selling involves very little lion around.

![]() |

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar by Gus Mager, November 25, 1906

(Collection of Paul Tumey) |

In this period of American newspaper comics, the fifth panel of a six panel Sunday was almost always the climax of whatever comic chaos ensued, usually filled with explosions, falling objects, food and paint splatters, and all manner of disaster. In Mager's strip, he underplays the comic moment and the result is far funnier than the over-reaching slapstick of the day. The image of Pete fleeing the lion inside the house is genuinely funny.

That same week, Mager drew a delightful Thanksgiving-themed vignette for Outcault's

Buster Brown, featuring his jungle animals.

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - Nov. 25, 1906 |

It's not clar if Mager simply didn't create a Pete episode for the following week, or if the newspapers I've been using to fill the missing gaps in my collection didn't run Pete for the week of December 2. In any case, here is the extra large

Buster Brown topper vignette Gus Mager drew that week, this time with a Christmas theme.

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - Dec.2, 1906 |

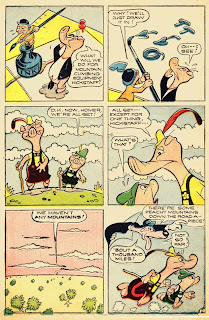

In the Pete episode of the following week, December 9, Pete attempts to sell stilts to diminutive pygmies. This seems like a good idea, but we know better...

![]() |

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar by Gus Mager, December 9, 1906

(Collection of Paul Tumey) |

Graphically, the above strip is a perfect sequential deconstruction of cultural logic. We move from verticals of Pete's world in panel one to the skewed slants of the pygmies. The last two panels are exponentially funnier without sound effects or speech balloons. Mager's 1906 Sundays show, perhaps for the first time, what Minimalism looks like in screwball comic strip form.

On December 9, someone besides Mager drew the

Buster Brown vignette, and so we move on to the last episode of

Pete, in which he attempts to sell a folding bed to jungle natives and draws the interest of a famished feline:

![]() |

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar by Gus Mager, December 16, 1906

|

The last panel, with the flattened, two-dimensional tiger pre-figures the sort of visual gags around plastic forms that would become a staple of 1930s and 1940s animated cartoons -- Mager, in his 1906 Sundays, was thinking like an animated film director would, twenty years after

Pete the Pedlar!

Even though his short run of Sunday funnies experiments ended on December 16, 1906, Mager continued to draw topper vignettes for

Buster Brown. In these last examples, Mager begins to draw two sequential vignettes, offering a rudimentary comic strip, boiled down to it's most basic elements. Here are the rest of Mager's

Buster Brown topper (again, these have nothing to do with the content of the Buster Brown comics that ran below them):

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - Dec.23, 1906 |

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - Dec.30, 1906 |

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - January 6, 1907 |

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - January 13, 1907 |

![]() |

| Gus Mager topper for Richard Outcault's Buster Brown - January 20, 1907 |

Mager returned to Sunday comics, with

Hawkshaw the Detective, about seven years after

What Little Johnny Wanted and

The Troubles of Pete the Pedlar. His new Sunday was a spin-off of his popular daily,

Sherlocko the Monk. Since the estate of Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the original Sherlock Holmes stories, vigorously defended the Sherlock Holmes copyright around 1913, Mager retreated from such a direct name and instead lifted from an obscure play in which a detective character is named "Hawkshaw." naturally, after some time, the word "hawkshaw" entered into popular American slang as a substitute word for "detective." Oddly, Mager's Sunday series offered a continuing story, while his dailies were one-shot gags. Here's an example of a Mager Sunday

Hawkshaw, from the first year of the strip:

![]() |

| Hawkshaw the Detective by Gus Mager - August 24, 1913 |

Mager's

Hawkshaw is good stuff, but it lacks the minimalist sensibility and sheer brilliance of his 1906 Sunday comics.

This concludes my 3-part monograph on Gus Mager's lost 1904-1906 Sundays. Despite the persistent comics archeology and the careful analysis offered in this monograph, two big questions related to this material remain: where did this stuff -- so unusual for the time -- come from, and why isn't the rest of Mager's subsequent output filled with similar sophistication?

In addition to having a long successful run with his

Hawkshaw Sunday (1913-1947, with some short breaks), Mager carved out a career for himself as a noted painter and member of the New York art world. He was friends with Paul Bransom (who took over Gus Dirks' bug comic strip after he killed himself) and Walt Kuhn, who was also a cartoonist who enjoyed working with animal characters. In 1913, Kuhn organized the seminal art exhibit at the Armory in New York City. Today, this show is legendary for being a snapshot of American art at the time and for influencing a new generation of artists. Kuhn included in this exhibit paintings by a few of his cartoonist colleagues who also wielded a brush: Rudolph Dirks (The

Katzemjammer Kids), T.E. Powers, and... Gus Mager. Mager had two paintings in the show, as shown in this scan from Kuhn's own copy of the program, now a part of the Archives of American Art.

Here's a self-portrait by Mager:

![]()

Gus Mager's life and work bears further scrutiny. In 1906, he was onto something and created a handful of comics that were artistic successes, generations ahead of their time. These comics embraced minimalism and other formal art elements to offer a simple but profound graphic style, anticipating the 1940s and 50s comics of Otto Soglow and the cartoons of the UPA Studio. The content of Mager's

What Little Johnny Wanted exposed the true power fantasies of every young boy, anticipating Maurice Sendak's classic 1963 book

Where the Wild Things Are and Bill Waterson's hit comic strip,

Calvin and Hobbes (1985-1995). But Mager, like most American cartoonists of the early 20th century, was first and foremost a popular artist who reshaped his vision and style until he hit upon something that pleased the general public. In doing so, he left behind his bold 1904-1906 experiments in comics, which have since been consigned to the dustbins of history. Even so, much of his work before, during, and after the period of the "lost Sundays" bears the stamp of a quirky, gifted artist and is worth study. Perhaps, someday, we'll have enough information and examples of Gus Mager's work to be able to answer all the questions I've raised about this fascinating American artist.

That is all,

Screwball Paul

paultumey@gmail.com

![]() |

| Gus Mager and canine friend - undated photo (circa 1910) |

- All text copyright 2013 Paul Tumey. No portion of this text may be used without written permission from paultumey@gmail.com

![]()