↧

A Hot Smokey Stover Fireman Sunday Page From 1939

↧

Energy Patterns Observed in a 1927 Screwball Salesman Sam Sunday by George Swan

Today I offer a nice paper scan of a very rare Salesman Sam Sunday by it's creator, George ("Swan") Swanson. I think this may be one of the last Sundays that Swan did before C.D. Small took over the series.

The page is a wonderful example of the streamlined, virtuoso cartooning style of George Swanson. Oddly bereft of its trademark background signs past the first two panels, this episode is all about movement and action.And simplification. The hands of Swan's characters are round blobs, feet are (Charles) Shulz-like black ovals, and the cityscape backgrounds are merely suggestive. The panels are filled with sweat drops, swirls, stars, movement lines, and sound effects. By 1927, Swan has mastered the screwball cartoon vernacular like few others.

In last week's Salesman Sam essay, we looked at the movement of energy in a Sam by C.D. Small. I made the point that screwball comics have wild and unpredictable (if logical) directions of movement when compared to comics of other genres. Here's how the movements map out in today's Swan comic:

It's all about conflict and comically explosive resolution. The top tier gives us two stable panels, with solid left-to-right movement. The third panel in the top tier initiates a conflicting movement.

After this, we get a tier of relatively minor explosions of random movement. The exaggerated takes shown here would be a highlight in many other artist's strips, but Swan had a much greater range for presenting visual chaos, placing him in the neighborhood of Milt Gross and Bill Holman.

The 3rd tier delivers more building conflict, which continues into the first panel of the last tier. Then, the last two panels explore the energy with the greatest velocity and number of directions of all the panels, proving a satisfying resolution.

All the Best,

Paul Tumey

The page is a wonderful example of the streamlined, virtuoso cartooning style of George Swanson. Oddly bereft of its trademark background signs past the first two panels, this episode is all about movement and action.And simplification. The hands of Swan's characters are round blobs, feet are (Charles) Shulz-like black ovals, and the cityscape backgrounds are merely suggestive. The panels are filled with sweat drops, swirls, stars, movement lines, and sound effects. By 1927, Swan has mastered the screwball cartoon vernacular like few others.

|

| March 27, 1927: One of the last Salesman Sam Sunday by George Swan . C.D. Small would continue the strip for another 10 years or so. (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

In last week's Salesman Sam essay, we looked at the movement of energy in a Sam by C.D. Small. I made the point that screwball comics have wild and unpredictable (if logical) directions of movement when compared to comics of other genres. Here's how the movements map out in today's Swan comic:

It's all about conflict and comically explosive resolution. The top tier gives us two stable panels, with solid left-to-right movement. The third panel in the top tier initiates a conflicting movement.

After this, we get a tier of relatively minor explosions of random movement. The exaggerated takes shown here would be a highlight in many other artist's strips, but Swan had a much greater range for presenting visual chaos, placing him in the neighborhood of Milt Gross and Bill Holman.

The 3rd tier delivers more building conflict, which continues into the first panel of the last tier. Then, the last two panels explore the energy with the greatest velocity and number of directions of all the panels, proving a satisfying resolution.

All the Best,

Paul Tumey

↧

↧

For Your Ice Only: A Cool 1926 Milt Gross Nize Baby Color Sunday Comic

From my own paper collection, I offer for today's Milt Gross Monday a deliciously screwball 1926 Nize Baby that totally cracked me up (cough cough).

Before the days of electrical refrigeration, people had small, thickly insulated cabinets in their home that stored slowly melting blocks of ice. This is how our grandparents and their parents kept food cool and fresh in America. My Southern mother still called her refrigerator an "ice-box," as do I -- to the amusement of some. Back in the day, you had to replace the ice as it melted -- it must have been quite a strenuous and messy task. Milt Gross, in today's comic, uses what was then a common chore as the basis for one of his terrific 12-panel operas of escalation, as Pop Feitelbaum tries in vain to get "de ice in de ice-box."

I think the comics of Milt Gross are superb in all periods of his career, but my favorite is the 1920s Sunday pages, which I think offer some of his wildest and funniest drawings. Today's 1926 comic is a great example:

It's interesting to me to note that the energy patterns in this comic are strikingly similar to the 1927 full page Salesman Sam Sunday by George Swanson that I posted yesterday. Tiers one and three are build-ups of conflict and energy, while tiers two and four are comedic explosions of the situation. Or, you could see this as a times-two repeat of a pattern -- a build-up and release, and then a bigger build-up and a larger explosive release. Instead of the physics-defying flip-take in Salesman Sam, here we get Pop's rage as he spanks his older son, Isidore.

Despite this pattern, visually the climax of the page is the wonderful 4th panel of Pop's circular skittering fall with the block of ice. Screwball comics are unpredictable in their movements, which is part of the delight of reading them.

We've seen in previous postings that Milt Gross liked to sometimes include his own version of a Rube Goldberg machine. The last panel once again shows Milt Gross' debt to to Rube Goldberg as he makes reference to Goldberg's popular comic panel, Foolish Questions.

Tomorrow, we'll take a look at Rube Goldberg'sFoolish Questions panel. Join me then! And be sure to stop by every Monday for a new Milt Gross comic!

Keeping my ice peeled,

Paul Tumey

Before the days of electrical refrigeration, people had small, thickly insulated cabinets in their home that stored slowly melting blocks of ice. This is how our grandparents and their parents kept food cool and fresh in America. My Southern mother still called her refrigerator an "ice-box," as do I -- to the amusement of some. Back in the day, you had to replace the ice as it melted -- it must have been quite a strenuous and messy task. Milt Gross, in today's comic, uses what was then a common chore as the basis for one of his terrific 12-panel operas of escalation, as Pop Feitelbaum tries in vain to get "de ice in de ice-box."

I think the comics of Milt Gross are superb in all periods of his career, but my favorite is the 1920s Sunday pages, which I think offer some of his wildest and funniest drawings. Today's 1926 comic is a great example:

|

| The Iceman Cometh in Milt Gross' Oct 24, 1926 Nize Baby (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

Despite this pattern, visually the climax of the page is the wonderful 4th panel of Pop's circular skittering fall with the block of ice. Screwball comics are unpredictable in their movements, which is part of the delight of reading them.

We've seen in previous postings that Milt Gross liked to sometimes include his own version of a Rube Goldberg machine. The last panel once again shows Milt Gross' debt to to Rube Goldberg as he makes reference to Goldberg's popular comic panel, Foolish Questions.

Tomorrow, we'll take a look at Rube Goldberg'sFoolish Questions panel. Join me then! And be sure to stop by every Monday for a new Milt Gross comic!

Keeping my ice peeled,

Paul Tumey

↧

Say, Are You Looking at A Computer? Rube Goldberg's Foolish Questions

Q: What's this, a blog?

A: No, it's a clam playing poker.

Presenting a look at Rube Goldberg's hit panel, Foolish Questions. Readers like me, who grew up reading Mad, will read these cartoons and see a connection between Foolish Questions and Al Jaffe'sSnappy Answers to Stupid Questions. Al has given Rube credit for the original idea, and has even admired Rube, famously calling him a "superJew."

The basic premise of Rube's influential cartoon panel can be gleaned in a second - a boob asks a question that shows s/he isn't really awake. Just as a Zen master might rap a sleepy student, Rube's characters answer in surreal, sarcastic phrases. Both sides of the formula are funny, and Rube's endless gallery of screwball grotesques make it all work brilliantly.

Rube credited fellow Evening Mail staffer, the columnist Franklin P. Adams, with the inspiration:

The first Foolish Question was numbered Number 1, and appeared October 23, 1908. Number 2 followed the day. Rube had a hit from the start. Earlier that year, he had emigrated across country from San Francisco after working as a sports cartoonist for about four years. With little experience, no job offer, and the ambition of youth, Rube faced down numerous rejections and landed a job with the sports editor at the new York Evening Mail, beginning a 14-year association that would prove mutually beneficial in a huge way, starting with the runaway success of Foolish Questions.

Between October 1908 and February 1910, the amazingly productive Rube Goldberg wrote and drew over 450 Foolish Question cartoons. Each cartoon featured new characters, a rich cast of extreme figures that are too short, too tall, too fat, too thin. Some with bulging eyes, others with black specks, and still others with inky black round sunglasses. Some hairless, some astonishingly hirsute. Writing in early 1909, Goldberg's fellow Evening Mail staffer, the cartoonist-illustrator Homer Davenport, said, "...funniest of all are the questions and answers of these bald-headed and hump-backed and knock-kneed people."

Here's a scan of a page from a recently acquired scrapbook that offers four Foolish Questions, all circa 1909-10.

The anonymous scrapbooker from a century ago had a good idea, grouping the panels. Within a year of its creation, Foolish Questions was appearing in newspapers across America, usually in groups of 2 or 3. Foolish Questions gets a 3-to-1 ratio compared to other cartoons in this 1909 edition of a Wisconsin paper.

Included in this set is a panel that is not likely to be reproduced in a collection, interestingly called Foolish, Foolish Questions:

A political conservative, Rube nonetheless was a humanist who believed in every individual's potential for good -- and the racism in his cartoons is no more extreme than what is easily found in most cartoons of the time.

Here's one from my own collection, from called "Those Ridiculous Questions," which suffers from a common weirdness of comics of the time (but not in Rube's work) where the speech balloons, when read left to right, are out of sequence.

In the comic above, you can see the writer really reaching to match Rube's surreal-sarcastic replies. It's interesting too, that this artist has made fledgling steps towards developing s single character as his particular fount of stoopid questions. Rube never did this -- the concept of his Foolish Questions panel was to show every conceivable type of person asking a dumb question-- underscoring the universality of human idiocy.

Starting July 25, 1909, the Chicago Tribune syndicated a 6-block of Foolish Questions for the color Sunday supplements of their subscriber papers. Sometimes the Sunday comic ran as Don't Some People Ask the Biggest Fool Questions?, a title lacking Rube's cadence and wit, and very likely written by a syndicate editor to fill the space.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and Rube's cartoons were so honored. Several imitations sprang up in 1909 and 1910. Here's an example of a Sunday half-page of a series unimaginatively called Foolish Foolish Questions that ran from Feb 14, 1909 to October 3,1909 (source: American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide, Allan Holtz, 2012).

Foolish Foolish Questions, drawn by "Sterling" and others, was distributed by World Color Printing, which interestingly published Rube's very first Sunday comic, a version of Mike and Ike called The Look-A-Like Boys (1907-1908). I wonder how Rube felt at being ripped-off by an outfit to which he had so recently belonged. Rube never seemed to let failure, rejection, or rip-offs slow him down.

In 1909, a classy cloth hardcover collection of Foolish Questions appeared, Rube's first book, and one of the very first cartoon collections published in America. Published by Maynard, Small, an Co., the volume is stuffed with reprints of selected favorites and sells for anywhere from $50 to $600 today. Occasionally inscribed copies can be found. The book was dedicated to Franklin P. Adams, the source of the original inspiration.

In 1909-circa 1912, Rube Goldberg also penned a new line of color Foolish Questions postcards. Judging by how often these 100-year old items turn up on eBay, a huge number must have been purchased.

Unscrupulous publishers ripped off the postcard series as well, quite clumsily:

At some point in the nineteen-teens, a Foolish Questions games came out, emblazoned with Rube Goldberg's jaunty, proud signature on the red cover:

Rube drew a figure on the games cover appropriately asked "What's this, a game?" The backside of a different figure asking the same question adorns the back of the cards. The game consists of a deck of cards, each with a different Foolish Question panel on the front. The cartoons were selected reprints, with the questions removed. The game involves correctly guessing the question, perhaps an influence on the game show, Jeopardy. In the example I've scanned above, the question is "Playing with your blocks, Elsie?" Here's the full version of the original cartoon, scanned from my paper collection:

In 1924, the Foolish Questions game was revived in a second edition, with fresh graphics, including a new Rube Goldberg designed cover, with a typically screwball answer:

A: No, it's a clam playing poker.

Presenting a look at Rube Goldberg's hit panel, Foolish Questions. Readers like me, who grew up reading Mad, will read these cartoons and see a connection between Foolish Questions and Al Jaffe'sSnappy Answers to Stupid Questions. Al has given Rube credit for the original idea, and has even admired Rube, famously calling him a "superJew."

The basic premise of Rube's influential cartoon panel can be gleaned in a second - a boob asks a question that shows s/he isn't really awake. Just as a Zen master might rap a sleepy student, Rube's characters answer in surreal, sarcastic phrases. Both sides of the formula are funny, and Rube's endless gallery of screwball grotesques make it all work brilliantly.

|

| circa 1909-10 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

Rube credited fellow Evening Mail staffer, the columnist Franklin P. Adams, with the inspiration:

"Did it ever occur to you what funny questions people ask?" observed Adams one afternoon. "You meet a fellow who's been out of town and say to him, 'Hello, you back again?' On an August day, with the thermometer at 100 even, a man is pushing a lawn mower around the front yard and oozing like a sponge, when some nut comes along and asks, 'Cutting the grass?' "

(from Rube Goldberg: His Life and Work by Peter Marzio, Harper and Row, 1973, p. 45)

The first Foolish Question was numbered Number 1, and appeared October 23, 1908. Number 2 followed the day. Rube had a hit from the start. Earlier that year, he had emigrated across country from San Francisco after working as a sports cartoonist for about four years. With little experience, no job offer, and the ambition of youth, Rube faced down numerous rejections and landed a job with the sports editor at the new York Evening Mail, beginning a 14-year association that would prove mutually beneficial in a huge way, starting with the runaway success of Foolish Questions.

|

| circa 1909-10 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

Between October 1908 and February 1910, the amazingly productive Rube Goldberg wrote and drew over 450 Foolish Question cartoons. Each cartoon featured new characters, a rich cast of extreme figures that are too short, too tall, too fat, too thin. Some with bulging eyes, others with black specks, and still others with inky black round sunglasses. Some hairless, some astonishingly hirsute. Writing in early 1909, Goldberg's fellow Evening Mail staffer, the cartoonist-illustrator Homer Davenport, said, "...funniest of all are the questions and answers of these bald-headed and hump-backed and knock-kneed people."

Here's a scan of a page from a recently acquired scrapbook that offers four Foolish Questions, all circa 1909-10.

|

| Rube Goldberg's Foolish Questions displayed on a 100-year old scrapbook page circa 1909-10 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

|

| The Janesville Daily Gazette, May 26, 1909 |

A political conservative, Rube nonetheless was a humanist who believed in every individual's potential for good -- and the racism in his cartoons is no more extreme than what is easily found in most cartoons of the time.

Here's one from my own collection, from called "Those Ridiculous Questions," which suffers from a common weirdness of comics of the time (but not in Rube's work) where the speech balloons, when read left to right, are out of sequence.

|

| Oct 3, 1909 - from collection of Paul Tumey |

Starting July 25, 1909, the Chicago Tribune syndicated a 6-block of Foolish Questions for the color Sunday supplements of their subscriber papers. Sometimes the Sunday comic ran as Don't Some People Ask the Biggest Fool Questions?, a title lacking Rube's cadence and wit, and very likely written by a syndicate editor to fill the space.

|

| Foolish Questions ran as a syndicated Sunday comic - July 25, 1909 |

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and Rube's cartoons were so honored. Several imitations sprang up in 1909 and 1910. Here's an example of a Sunday half-page of a series unimaginatively called Foolish Foolish Questions that ran from Feb 14, 1909 to October 3,1909 (source: American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide, Allan Holtz, 2012).

| A not so "Sterling" rip-off of Rube Goldberg's Foolish Questions- February 21, 1909 |

Foolish Foolish Questions, drawn by "Sterling" and others, was distributed by World Color Printing, which interestingly published Rube's very first Sunday comic, a version of Mike and Ike called The Look-A-Like Boys (1907-1908). I wonder how Rube felt at being ripped-off by an outfit to which he had so recently belonged. Rube never seemed to let failure, rejection, or rip-offs slow him down.

In 1909, a classy cloth hardcover collection of Foolish Questions appeared, Rube's first book, and one of the very first cartoon collections published in America. Published by Maynard, Small, an Co., the volume is stuffed with reprints of selected favorites and sells for anywhere from $50 to $600 today. Occasionally inscribed copies can be found. The book was dedicated to Franklin P. Adams, the source of the original inspiration.

In 1909-circa 1912, Rube Goldberg also penned a new line of color Foolish Questions postcards. Judging by how often these 100-year old items turn up on eBay, a huge number must have been purchased.

Unscrupulous publishers ripped off the postcard series as well, quite clumsily:

|

| The original Foolish Questions game - circa 1912-19 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

|

| circa 1909-10 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

In 1924, the Foolish Questions game was revived in a second edition, with fresh graphics, including a new Rube Goldberg designed cover, with a typically screwball answer:

In the summer of 1913, Rube took his first trip to Europe. The Evening Mail paid for the trip, and Rube faithfully mailed back a new cartoon series he called Boobs Abroad (after Mark Twain's European travelogue, Innocents Abroad). As we can see, in this example scanned from my paper collection, Rube integrated Foolish Questions as a panel within the cartoon series, and linked it thematically.

|

| Rube cleverly links his Foolish Questions series with his Boobs Abroad series - 1913 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

Rube continued to write and draw Foolish Questions until 1934. The series peaked in 1910, and he had a second big hit with I'm the Guy, followed by an astonishing series of inspired cartoon series and panels. Foolish Questions remains a notable standout among Goldberg's many inspired creations. As Homer Davenport admiringly wrote in 1909:

"What a simple creation is a parody, and what a world of reality is there in Goldberg's Foolish Questions series!"

Say, is this the end?

-Paul Tumey

↧

H.M. Bateman and The Speed of Life: Four Cartoons from 1923

Here are four pages of the brilliant English cartoonist H.M. Bateman's cartoons from 1923, scanned from a scrapbook I recently acquired. I believe these are all from the pages of Life, a black and white humor magazine that preceded the more famous photo-based Life Magazine.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

ANNOUNCEMENT! We're changing direction at the Masters of Screwball Comics blog. Instead of a daily posting, we'll shift to a weekly Sunday posting for the fall of 2012, to be called "Screwball Sunday." This will mimic a Sunday newspaper comics section, but will be assembled by me and be composed entirely of noteworthy screwball comics from all eras, with notes by me (of course). I will occasionally write and post illustrated essays on screwball comics as well. Tune in this Sunday for our first SCREWBALL SUNDAY!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

As I wrote in an earlier posting on H. M. Bateman (1882-1970), it may be too much of a stretch to classify him as purely screwball, but there's no doubt his work influenced screwball cartoonists. Consider how the the panel I've excerpted above compares to this scene from Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder's classic "Restaurant!" story from Mad #16 (1954)

While Elder has created a dense tapestry of sight gags, the basic energy is the same as Bateman's panel. Both cartoonists are saying something about the acceleration of modern life.

There is so much to savor in Bateman's work. Like Milt Gross, each drawing is funny on it's own, but also contributes to a glorious escalation of comedic chaos. Bateman himself said that his cartooning was "going mad on paper."

The four pages in this article are chosen because they all depict people struggling madly to get somewhere, something that was relatively new in 1923. Bateman, who was born in 1882, saw the rise of the automobile. In this cartoon, he chronicles the plight of the pedestrian plagued by motorized vehicles at every turn.

|

| From Life, circa 1923 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

The gag is that our nimble pedestrian is run over by an "out of date vehicle." This cartoon says there's no avoiding change, and if you try, you will suffer. Here's another Bateman, beautifully composed and rendered, that depicts another battle between a pedestrian and a car-clogged street:

|

| From Life, circa 1923 (from the collection of Paul Tumey) |

I love the manic, focused -- one might say mad -- look in the pedestrian's face. It requires madness to triumph in a world that turns a man out for a walk into a pedestrian.

Finally, here's an entire group of individuals who have completely adapted to the increased velocity of life. We begin with a group of seven people, all interacting civilly and having a pleasant time. As with William Golding's Lord of the Flies, the trappings of civility are shed when the group must combat each other to survive -- but in the case of the cartoon, they are only competing for a ride on the crowded subway.

They emerge from the underworld, disheveled but willing to embrace civilization once again. The astonishing third tier of the subway battle mirrors the energy of a subway train itself, screeching, jolting, careening, speeding through the darkness.

This was the world of London, New York, Boston, or any other major city in 1923.

Today, it seems the speed of life continues to accelerate -- but instead of fighting for our survival like fleeing or fighting animals, we seem to be in a narcotic haze of Internet, TV, sugar, caffeine, alcohol, drugs, memes, constantly looming disaster -- in short, many of us in the big city are subdued, bored, and possibly even depressed. Here's a photo I took while waiting for a subway train in New York City a few weeks ago.

And here's a shot I sneaked on the train -- looked how bored and tuned out the people are:

Maybe it was like this for people in 1923. Or 1823. Our time certainly has no claim to being the only era of numbing stress in humanity's history.

Today's last H.M. Bateman cartoon once again revolves around transportation. It depicts the ever increasing happiness of a traveler with some priceless drawings and a beautiful opera of escalation. As our Englishman gets further and further away Canada, he becomes happier and happier.

Our traveler has died from happiness! It seems in 1923, Bateman was acutely aware of how technology seemed to aid the human ego in its need to constantly be somewhere else, distracted, and gratified.

|

| H. M. Bateman in 1931 |

In The Man Who Was H. M. Bateman (Webb and Bower, Great Britain, 1982), Anthony Anderson observes:

"Bateman by no means rejected all progress: he thought scientific advance exciting, and, for example, considered the first Moon landing the most wonderful feat of his lifetime - he never stopped talking about it. It was the ugly, leveling, concrete and tarmac side of progress that he hated, and it upset him so much that it was without doubt one of the major factors in his decision to quite England." (p. 202)

Bateman moved to the island of Malta in his later years, where he enjoyed a quite life as a painter. His work was a major influence on Harvey Kurtzman, who in turn influenced scores of important cartoonists and humorists.

Yours in Screwballism,

P.C. Tumey

↧

↧

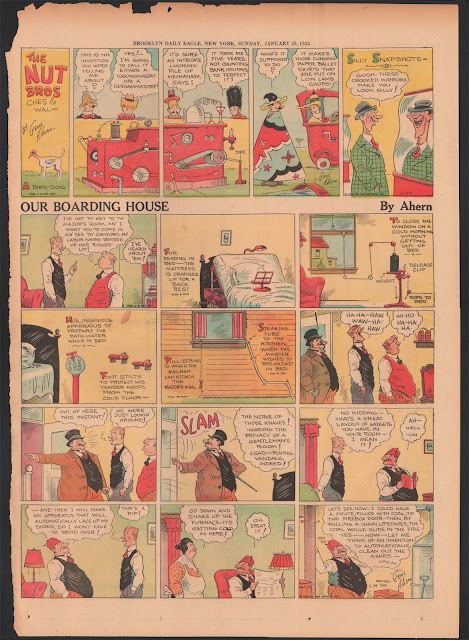

Screwball Sunday Supplement V17 No 148 - Ahern,Goldberg,Gross, Bradford,Holman,Capp

A big thank you to Dan Nadel and the folks at the The Comics Journal for the link - your support is greatly appreciated and very helpful.

ANNOUNCING a change in direction. Instead of a daily posting, we have shifted to a weekly Sunday posting for the fall of 2012, to be called "Screwball Sunday." This will mimic a Sunday newspaper comics section, but will be assembled by me and be composed entirely of noteworthy screwball comics from all eras, with notes by me (of course). The first issue is above.

I will also occasionally write and post illustrated essays on screwball comics as well, as time and inspiration allow.

To be clear, the pages above are all designed by me, Paul Tumey - they are not scans of any existing paper document (although they contain plenty of scans from my paper collection that you will only find on this blog).

Tune in every Sunday for a NEW collection of startling, saliva-spewing screwballistic delights.

Please remember to help promote this blog if you can. A link, a mention, or just a comment -- it all helps. Let's spread the word, Alphonse. I think Alphonse is a purrfectly good word to spread, although butter is margarinely butter.

Hope you henjoy! Drop me a line or a comment and let me know what you think. paultumey@gmail.com

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

My friend and fellow comics scholar Frank Young has co-authored with David Lasky an outstanding graphic novel, The Carter Family: Don't Forget This Song (from Abrams ComicArts). The book will be reviewed in the October 14 issue of Time Magazine, along with Chris Ware's landmark work, Building Stories.

I've read both of these books and highly recommend them.

Click here to read Frank and David's absorbing post detailing the enormous craft that went into a single page of their book.

↧

Screwball Goes to the Dogs - Doc Syke, Milt Gross, Swinnerton, and Smokey! (Vol.1 No. K9)

Welcome to the second Screwball Sunday Comics Supplement! In this issue, we have literally gone to the dogs. Here's your chance to bone up on some forgotten screwball classics. With one exception, these are all scans from my own paper collection, and the first time these appear on the Internet. This faux newsprint supplement is designed by me, Paul Tumey.

In this survey of cartoon screwball dogs, we note the prevalence of black-spotted orange dogs. In every example, we also see dogs interacting with us fellow humans. One of the surprising aspects of screwball comics is how they often reveal the underlying truths of life. In this weeks' Sunday supplement, we see cartoonists turning over and over to the theme of dogs and people as constant companions.

Please let me know how you like this. Your comments and emails are so important to me!

paultumey@gmail.com

And, if you have the chance to plug this blog, it would help spread the word about these worthy comics.

The day this post went up, Google celebrated Winsor McCay's 107th birthday with an astonishingly good point-and click interactive comic.

Screwily Yours,

Nuthouse Tumey

↧

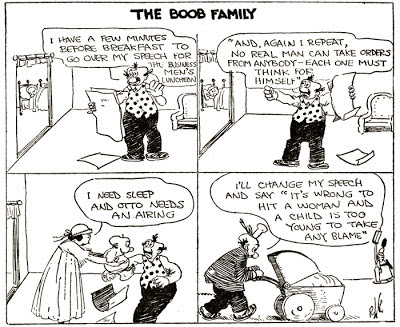

Screwball Sunday Supplement Vol. 3 No. 33 - The Squirrel Cage, Swinnerton's Hilarious SAMs, & Count Screwloose

GREETINGS FROM THE LAUGHING ACADEMY!

Welcome to the third issue of our Screwball Sunday Supplement. This issue is packed with comics that ALL have produced guffaws and laffs amongst me self and me pals.

We kick off with a superb Milt Gross Count Tooloose that could well be the prototype for Tex Avery's classic Droopy cartoon, "Dumb-Hounded." We also get a Milt Gross Banana Oil topper. This was a very popular strip in itself back in the day, with folks saying "banana oil!" instead of "bullshit!"

In the interior spread, we get the extra-special treat of 4 Squirrel Cages, all from the 1946 detour from Foozland into Goonia. This is Gene Ahern at his most inspired, most trippy, most sublimely screwball.

On the the back page, we find two truly funny rescued 1905 Jimmy Swinnerton gems from the Platinum Age of American newspaper comics that I hope you will take the time to read, as I think they are something special, racial stereotypes aside.

Swinnerton's SAM strips echo Gross' Banana Oil and Count Screwloose comics in that they both provide a surrogate observer into the strip in the form of the Count, and Sam. Where black American Sam laughs at pomposity, Jewish American Screwloose is aghast at hypocrisy. Sam may have the more light-hearted response, but in all fairness, he "mp-mp-mps" in an earlier and more innocent era, before the horrors of the 20th century transpired.

Just as Sam and The Count are doorways into their comic strip worlds, Ahern's Paul Bunyan-as-bewitched-gnome is a surrogate figure for us in The Squirrel Cage, through which we can comfortably explore the weird worlds of Foozland and environs. Ahern fractally inserts a multitude of additional doorways into his strip, going ever deeper into the labyrinth, until it's impossible to tell the dream from the dreamer -- do we dream of the snarky citizens of Goonia, or do they dream of us?

Ump, Ump ~

Paul Tumey

↧

Screwball Sunday Supplement - Hairbreadth Harry, Petty Patty, Squirrel Cage, Dave's Deli, and Goldberg

Welcome to the fourth Screwball Sunday Supplement. This issue features two consecutive examples from 1913 of the early screwball masterpiece, Hairbreadth Harry, by C.W. Kahles, in which all the water is drained from an ocean and much silliness ensues. The strip's title, "Hairbreadth Harry" comes from the fact that the hero always escapes from mortal danger by a hair's breadth, a cliche even in 1913.

We also see a rare example of Rube Goldberg's comic strip advertisement for Pepsi Cola, a late Squirrel Cage, and a terrific example of the forgotten romantic screwball comic Petting Patty by Jefferson Machamer. All this, plus a mind-blowing Milt Gross!

As I am fond of clucking, HEN-joy it!

Screwily,

Paul Tumey

↧

↧

A Rube Goldberg Machine For Voting - Election Special

To commemorate election day 2012 in the United States, I offer to the world an impressive screwball machine that Rube Goldberg invented for recording votes. Click on the cartoon to enlarge.

|

| Voting Machine cartoon by Rube Goldberg, circa 1920s |

"When all clerks are unconscious, election is over."

I don't have an exact date of publication for this cartoon. I would say that it's from the 1920s. Rube, a Pulitizer Prize winning editorial cartoonist (1948) promoted a largely conservative agenda. In his humorous cartoons, however, he often transcended political factions and commented on the screwball side of life, as he did in the above invention cartoon, which works both as a typical "Rube Goldberg" machine and a sarcastic comment on our election process.

It's one of his best. His biographer, Peter Marzio, placed it on the front endpaper of his book, Rube Goldberg His Life and Work (New York: Harper and Row, 1973).

Need I urge my readers to vote today? Perhaps you'll get lucky and encounter a wacky screwball machine!

Your Fellow Screwball American,

Paul C. Tumey

↧

Pigging Out on Jimmy Swinnerton - A Rare 1912 Color Sunday

James Swinnerton had a remarkable appeal in his screwball drawings of dogs and children. Here's a very rare color Sunday page from 1912 that features plenty of hilarious kids and pigs, plus a great bulldog. Robert Beerbohm has published several letters from old-time cartoonist Ernie McGee, who points out in one letter that the dogs in a comic authored by another cartoonist (I think it was Dirks) were drawn by Swinnerton. McGee said that no one could render a funnier bulldog, and Swinnerton was occasionally asked to "guest-star" in a fellow cartoonist's strip by drawing in some of his bulldogs.

This scan is from my own paper collection. The comic itself is extremely fragile and fell apart as I scanned it. I'm happy to be able to preserve these treasures. Hopefully more folks will come to appreciate the greatness of Jimmy Swinnerton and the works of his fellow screwball masters shared on this blog!

This scan is from my own paper collection. The comic itself is extremely fragile and fell apart as I scanned it. I'm happy to be able to preserve these treasures. Hopefully more folks will come to appreciate the greatness of Jimmy Swinnerton and the works of his fellow screwball masters shared on this blog!

|

| Little Jimmy by James Swinnerton August 18, 1912 (from the collection of Paul C. Tumey) Even though it's not named as such, this page is part of Swinnerton's long-running Little Jimmy series, sometimes spelled as Little Jimmie. Jimmy's often tasked by his father with minding the baby, or going on an urgent errand. Jimmy is easily, always, and inevitably side-tracked, and the result is often comic chaos. The scene in panel 8, where the father sees what he thinks is his baby playing with the piggies is screwballism par excellence. This sort of set-up is exactly what Milt Gross would recreate about 25 years later. In Gross' case, the father's panic would be hugely exaggerated, with hair standing on end, hat flying into the stratosphere, and the entire body stiff as a board in shock and three feet off the ground. With Swinnerton, even though the comic exaggeration is several notches below what we tend to expect in screwball comics, the basic framework for this exaggerated humor is solidly present. Swinnerton's story is fascinating. He started out as one of the very first newspaper cartoonists in New York, working for William Hearst, also a close friend. Swinnerton was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1906, and Hearst -- in great concern -- paid for his relocation to the arid desert out west. What a journey and a huge cultural shift that was for "Little Jimmy!" Swinnerton learned to love the west and spent weeks hiking and sleeping under the stars. he kept drawing his cartoons and would wait for trains to pass by when we came upon a track. He'd hand his cartoons to the train conductor, who would get them back to Hearst in New York. The very cartoon we share today may have undergone just such a cross-country journey. Swinnerton's cure worked, and he lived until 1974. He shared his love of the desert, luring many fellow New York cartoonists to the ancient canyonlands. Swinnerton was the guy who introduced George Herriman to the desert and, as such, is probably responsible for the magical landscapes of Krazy Kat. Swinnerton started out as a charming cartoonist who could spin out screwball and slapstick with layers of disarming cuteness. After a while, his work became more spiritual and lyrical, and he integrated the desert and American southwest into his cartoons. He was highly sympathetic to the various American Indian cultures he experienced first-hand. Here's some breathtaking Little Jimmie dailies from 1933, in which Jimmy and his kid and animal friends have somehow migrated to the southwest: Click here to hear a great rare 1963 audio interview with Swinnerton about his life and career. Just wait till we get home, Screwball Paul |

↧

The Secret History of Screwball: A Squirrel's Progress

While Gene Ahern's world of Our Boarding House and Room and Board explores the archetypes of early 20th century small town America, his multi-year Foozland continuity in The Squirrel Cage vastly and mind-blowingly expands his canvas, offering an allegorical journey through an entire alternate universe.

___________________________________________

Note: Georgian folksinger and comics scholar Carl Linich has posted 10 of the rare Paul Bunyan strips from Gene Ahern's The Squirrel Cage on his blog here.

____________________________________________

Unique among American newspaper comic strips, The Squirrel Cage has a structure that allows broad philosophical and social commentary in the innocent guise of a goofy Sunday comic. Where strips like Pogo and Doonesbury offer sharp topical political commentary, The Squirrel Cage provides a more philosophical-poetical -- almost a Shakespearian perspective on social trends, morality, and government. One hesitates to say how much of the wisdom expressed in The Squirrel Cage is intended or deliberate.

To me, it feels like Ahern in the 1940s knew he was on the mainline connection to his subconscious, and somehow was able to make it flow for years, while at the same time meeting (just barely, and with decreasing sales) the demands of the American newspaper comic strip market. A remarkable feat. Contrast the dreamlike play of a Squirrel Cage comic with the pointed, pun-drenched satire of a Pogo Sunday, and you can see a profound difference between an artist offering superb craftsmanship and an artist revealing his subconscious. There's a very real link between Ahern, psychedelic Underground comics of the 1960s, and the free-flowing stream-of-consciousness social and spiritual commentaries of Steve Willis. While I love Walt Kelly's work, for my money, the surreal, screwball association of Ahern's comics are more valuable to me, because they offer a way to bypass the limitations of rational thinking and reveal something deeper, weirder.

Reading The Squirrel Cage is exciting because it's delightfully odd, and that oddness is rooted in a dreamlike exploration of reality itself. Humor at its best is always based on sharp insights about the world. Ahern's humor grew more sophisticated in this way with each passing year. Finding poetic-philosophical meditations in a forgotten old screwball newspaper comic strip is tantamount to discovering the profound philosophical-religious explorations of Philip K. Dick that were originally packaged as 1950s and 1960s pulp magazine and cheap paperback science fiction.

In the Foozland strips of The Squirrel Cage, Gene Ahern -- a cultured man who (according to his press) used his cartoonist's salary to collect paintings by European masters -- presents a kaleidoscopic view of a fantastic world. His landscapes shift from panel to panel. George Herriman's Krazy Kat is famous for its ever-morphing landscapes; Ahern's Squirrel Cage is virtually unknown but employs the same device with equal artistic success. The multi-year aimless drift through Foozland offers hundreds of bizarre characters, odd plants and animals, and distorted physical laws that reveal, in a disguised and surreal way, underlying truths about our social systems and the subjective nature of reality.

Where Our Boarding House (1922-1936) and later Room and Board (1936-1953) are centered on the delightfully self-deluded world of Major Hoople/Judge Puffle, The Foozland strips of The Squirrel Cage (1936-1953) are subversively directed outward, with a constant focus on the environment instead of the interior world of a central character.

The Paul Bunyan Gnome

The closest thing we have to a central character in the Foozland strips of The Squirrel Cage is the red-yellow-black clad gnome (the same color scheme worn by Jack Cole's form-bending Plastic Man).

Attentive readers of The Squirrel Cage know the little gnome -- a doppleganger for the the Little Hitch-hiker (who also appears in the Foozland strips) -- is actually Paul Bunyan, the mythic logger giant from American tall tales!

This alone is a wonderful surreal gag, but Ahern dropped it after a couple of years. After Paul Bunyan tangles with an ill-tempered witch, he is reduced to a pint-sized lawn-ornament style gnome and banished to the mysterious country of Foozland, where the laws of humans and nature are radically different from our collective reality. After this transformation, the strip never again refers to the gnome as Paul Bunyan. He is essentially a cipher, with no name, no purpose, and no character -- the very opposite of the richly human Major Hoople and Judge Puffle.

The Bunyan-gnome initially wanders Foozland with a vague purpose of returning to his own world and form. This purpose becomes hazy, and finally forgotten as he is subsumed into the dreamworld of Foozland. Reading the Foozland strips in sequence reveals a "hidden" story of a character lost in a dream and unable to wake up.

Bunyan-gnome occasionally breaks through the borders of Foozland, but instead of returning to our universe, he finds himself in places like Goonia, which is merely another country in the un-named alternate universe. The strip is filled with a never-ending labyrinth of magic doors, caves, tunnels, and stairways that force the gnome (and the reader) to abandon all sense of direction and bearing. Ahern has created on paper a metaphor for what living itself feels like (at least living unconsciously), with its unexpected twists and turns that lead us through a daily parade of bewildering dead-ends in our search for security and reassuring (and non-existent) consistency.

The main visual symbol of travel in the Foozland strips is the ever-present Road, on which characters mostly travel left-to-right, in a mirror-image of the way English-speaking peoples read symbols and (most) sequential graphic narratives.

Minor masterpieces like The Squirrel Cage, because they have been ignored and forgotten, appear to spring up from nowhere, but this is far from the the truth. This lost comic strip actually continues a centuries-old tradition of allegorical storytelling, and traces to some surprising cultural cousins on the nut-laden screwball family tree.

The Origins of Foozland: Bunyan to Bunion

In considering the possible antecedents of Gene Ahern's Foozland, it helps to recognize the strip has an allegorical tone. In some cases, the strips may function as an allegory -- which is a story structure in which characters symbolize ideas and concepts -- and some cases, the strips only assume an allegorical tone, because at their heart, they are more surreal, eschewing any direct, one-to-one correlations between character and concept.This was, after all, first and foremost, entertainment for the masses.

The allegorical tone of Gene Ahern's Foozland strips can be traced back to A Pilgrim's Progress, a little-known series by Winsor McCay, one of the greatest artists of the medium.

According to Allan Holtz's American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide (2012), A Pilgrim's Progress ran on weekdays from June 26, 1905 to May 4, 1909.

In McCay's A Pilgrim's Progress, we see a tall, gaunt man clad in black carrying a suitcase called "Dull Care." As with the gnome-Paul-Bunyan in The Squirrel Cage, he seems to almost always journey from left to right, on an eternal Road. McCay's Pilgrim (who is sometimes referred to as "Mr. Bunion", a play on John Bunyan's name) ) encounters one tortured soul after another, and is unable to put his suitcase down to help. In the example shown above, we see a man driven crazy by his own outrage at the world's injustices -- unable to see that his "truth-telling" is really a form of blindness. He's an allegorical figure representing mindless blaming. Other people our Pilgrim encounters represent greed, gluttony, lust, hypocrisy, and so on. The Pilgrim himself respresents Everyman, who is burdened with the weight of the world and "worries for the entire universe."

Signing his series as "Silas," McCay reminds me of Hank Williams posing as "Luke the Drifter" -- both men adopting a new persona to deliver sermons in the form of entertainment.

In his lilting musical sermon, "I've Been Down That Road Before," Hank Williams recites:

The image of a man's head swollen so large seems oddly resonant with Winsor McCay's dream imagery, not to mention some scenes from the Foozland stories which explicitly feature swelled heads and other physical transformations. Compare William's "doggone big" head with McCay's giant hammer in the last panel of the Pilgrim's Progress example above.

Note also William's use of the allegory of the Road as spiritual path. This is the same road McCay's Pilgrim and Ahern's Paul Bunyan-gnome travel.

Williams adopted the alter-ego of Luke as a way to deliver sermons to 1950s America without lessening the marketability of his name, popularly associated with "honky tonk" country and western songs like "Your Cheatin' Heart."

You can here the entire Luke the Drifter sermon of "I've Been Down That Road Before," here:

The "Dull Care" suitcase Winsor McCay's pilgrim totes -- a burden he cannot share -- also resonates with another 20th century musical icon, the 1968 song The Weight. Composed and performed by The Band, and appearing as the centerpiece of their first album, Music From Big Pink, the song was inspired by Luis Bunuel's symbolic films of spiritual quests through absurd situations. The Weight seeks to create an allegory of a burdened man wandering, very much like McCay's Pilgrim and William's Luke the Drifter. The wanderer carries a "bag" (which in 1968 America had a double meaning, since "bag" was a slang for "purpose" -- as in "what's your bag, man?") and encounters a dizzying variety of odd characters.

One of the characters in The Weight is named Luke, perhaps a tip of the cowboy hat to Hank.

The actual full title of McCay's strip is A Pilgrim's Progress by Mr. Bunion. The readers of 1905-1909 would have been more familiar with the comical, self-depreciating reference to John Bunyan, author of the 17th century bestseller, A Pilgrim's Progess.

Bunyan, who began writing Pilgrim's Progress while in prison for preaching without a license, would have fit right in with the strange characters of The Weight, McCay's worlds, and Foozland. He spent much of his adult life seeking to redeem his wild youth in which he committed such immoral acts as dancing and bell-ringing. He was -- to give him credit -- legendary among his young peers for his ability to swear like a sailor. Bunyan apparently turned his wordsmithing talent to a higher purpose, and wrote one of the most famous books in the English language, A Pilgrim's Progress, a book that perhaps the younger Bunyan might have said was damned good and fucking weird.

Here's a small part of the Wiki summary of the book:

The witnessing of humanity's suffering and unconscious insanity that McCay's Pilgrim provides is not that different from the adventures of Milt Gross' Count Screwloose, who regularly escapes from the looney bin (sometimes with a Rube Goldberg machine) only to see so much craziness in the outside world that he is happy, at strip's end, to return to the relatively sane world of the Nuttycrest asylum for the mentally disturbed.

When you look at it, there seems to be some sort ongoing discussion, first in strange books and then in strange comics, about journeys through screwball worlds.

Can it be mere co-incidence that Ahern shifted his wacky screwball strip about two inventors and a little hitch-hiker into an allegory by way of a character called Bunyan? Perhaps the DNA of the secret history of screwball comics looks something like this:

When we consider the dreamlike imagery found in The Squirrel Cage (and The Nut Brothers, an earlier Ahern surreal romp) it makes sense, then to look at the first page of the first publication of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress and see the word "dream" write large:

The Fun of Going Nowhere

When he created the Foozland continuity in The Squirrel Cage, Ahern built a serial dream that lasted years and went nowhere. The very title of the strip is a natural extension of the many squirrel and nut labels used in screwball comics, from Rube Goldberg's Boob McNutt to Ahern's own Squirrel Food and Nut Brothers. But there's another layer to the strip's title, since a squirrel cage is a confining environment in which a squirrel can run forever without ever getting anyplace -- just like the Buyan-gnome in Foozland.

With his invention of Foozland in The Squirrel Cage, Gene Ahern built one of the most elegant and incisive tools for social commentary in all of American comics. The strip below, from 1945, the first year of the Foozland continuity (at some point, something must be said about the meaning of Foozland's birth coinciding with the end of World War 2 and the arrival of The Bomb), provides an allegory on leadership with some dreamlike lampoons of government and social responsibility.

Let's take a closer look. In the first panel, we begin with the Little Hitch-hiker and his classic existential nonsensical question: "Nov shmoz ka pop?" Ahern almost always drew an absurd object next to the Hitch-hiker, and here we see a giant block of ice, defying the laws of physics by not melting -- a visual gag Ahern used many times in The Squirrel Cage -- nevermind WHY the Little Hitch-Hiker has a block of ice with him. In the first moments of the strip, we are already confounded. As the Hitch-hiker hitchhikes, the King of Foozland walks The Road, left to right, declaring he is taking a day off. because he is king, the plants and animals must bow to him. His train is kept from touching the ground not by a servant, but by a little wheel.

The impulsive King of Foozland encounters the Bunyan-gnome, who is always on The Road, and makes him King. The crowned gnome, now bowed to, has no idea how to be a King. He stands on a path that has mysteriously developed a set of steps leading down - an allegorical symbol that he may be headed for a moral descent if he doesn't use his newly acquired power well.

Next, the King must sign a law -- the lawmaker acknowledges the power of the crown, whil ealso acknowledging that the gnome is not the real King. The law itself is comically huge, a giant scroll that is

so heavy (the Weight) he struggles to carry it.

The law is against beards, but as the lawmaker explains this, a long full beard appears on his face.

In the early 1990s, I lived in Leominster, Massachusetts, a small town filled with plastic factories and -- ironically -- famous as the birthplace and home town of Johnny Appleseed. One day, while walking home through the city cemetery, I came across a curious gravestone:

It seems that in the late 18th century, Leominster citizen Joseph Palmer was intolerantly attacked by his fellow townsmen for wearing a full beard. The book, Weird New England, tells us his clean-shaven peers thought Palmer's full beard was "antisocial and sinful." This resonantes with John Bunyan's self-persecution for dancing and bell-ringing. He was jailed for causing a disturbance of the peace and kept for a year. Palmer was finally released, refusing to cut his well-groomed beard. His jailers tied him to a chair and threw him from the jail. The "no-beard" law in Gene Ahern's April 8, 1945 Squirrel Cage reminds me of Palmer. In effect, when the beard magically appears on the man who wants to outlaw beards, something is being said about human versus moral law. Realizing he has a beard (without ever questioning why or how that he could grow a long beard in a second), the lawmaker instant shifts his focus to outlawing people WITHOUT a beard -- thus he has become an allegorical figure for Intolerance. In the background a Herriman-esque tree appears to have a fuzzy hat, or perhaps a beard.

Realizing that he almost signed into law something that "put people in trouble," the gnome begins to question whether it is right for him to wear the crown. There's an old saying that the best leaders are those that do not wish to lead -- it seems the gnome has common sense, and perhaps even moral sense. The tree he touches is multi-colored and oddly shaped -- it seems to resonate with a meaning, but its unclear what that meaning may be.

In a small heroic gesture, the gnome divests himself of the power and responsibility of rulership, and bestows it upon a scarecrow -- a "fake" human.

In the last panel, the former King of Foozeland, now a mere subject, bows to the crowned scarecrow. It's almost as if there's no importance placed on who leads, but only that thereis a leader -- even if it's only a scarecrow. Woody Guthrie once famously said, when asked of about his political affiliation, "right wing, left wing, chicken wing -- it's all the same to me." Of course, this was nonsense, since Guthrie was a well-known radical activist of his time, but in this nonsense -- like the nonsense of The Squirrel Cage -- is valuable -- and shocking -- wisdom.

Your Screwball Scribe,

Paul Tumey

All text copright 2012 Paul C. Tumey

___________________________________________

Note: Georgian folksinger and comics scholar Carl Linich has posted 10 of the rare Paul Bunyan strips from Gene Ahern's The Squirrel Cage on his blog here.

____________________________________________

Unique among American newspaper comic strips, The Squirrel Cage has a structure that allows broad philosophical and social commentary in the innocent guise of a goofy Sunday comic. Where strips like Pogo and Doonesbury offer sharp topical political commentary, The Squirrel Cage provides a more philosophical-poetical -- almost a Shakespearian perspective on social trends, morality, and government. One hesitates to say how much of the wisdom expressed in The Squirrel Cage is intended or deliberate.

To me, it feels like Ahern in the 1940s knew he was on the mainline connection to his subconscious, and somehow was able to make it flow for years, while at the same time meeting (just barely, and with decreasing sales) the demands of the American newspaper comic strip market. A remarkable feat. Contrast the dreamlike play of a Squirrel Cage comic with the pointed, pun-drenched satire of a Pogo Sunday, and you can see a profound difference between an artist offering superb craftsmanship and an artist revealing his subconscious. There's a very real link between Ahern, psychedelic Underground comics of the 1960s, and the free-flowing stream-of-consciousness social and spiritual commentaries of Steve Willis. While I love Walt Kelly's work, for my money, the surreal, screwball association of Ahern's comics are more valuable to me, because they offer a way to bypass the limitations of rational thinking and reveal something deeper, weirder.

Reading The Squirrel Cage is exciting because it's delightfully odd, and that oddness is rooted in a dreamlike exploration of reality itself. Humor at its best is always based on sharp insights about the world. Ahern's humor grew more sophisticated in this way with each passing year. Finding poetic-philosophical meditations in a forgotten old screwball newspaper comic strip is tantamount to discovering the profound philosophical-religious explorations of Philip K. Dick that were originally packaged as 1950s and 1960s pulp magazine and cheap paperback science fiction.

In the Foozland strips of The Squirrel Cage, Gene Ahern -- a cultured man who (according to his press) used his cartoonist's salary to collect paintings by European masters -- presents a kaleidoscopic view of a fantastic world. His landscapes shift from panel to panel. George Herriman's Krazy Kat is famous for its ever-morphing landscapes; Ahern's Squirrel Cage is virtually unknown but employs the same device with equal artistic success. The multi-year aimless drift through Foozland offers hundreds of bizarre characters, odd plants and animals, and distorted physical laws that reveal, in a disguised and surreal way, underlying truths about our social systems and the subjective nature of reality.

Where Our Boarding House (1922-1936) and later Room and Board (1936-1953) are centered on the delightfully self-deluded world of Major Hoople/Judge Puffle, The Foozland strips of The Squirrel Cage (1936-1953) are subversively directed outward, with a constant focus on the environment instead of the interior world of a central character.

|

| A typical Gene Ahern Our Boarding House episode, encased in the limited -- but comically rich -- world of Major Hoople's delusions... |

The Paul Bunyan Gnome

The closest thing we have to a central character in the Foozland strips of The Squirrel Cage is the red-yellow-black clad gnome (the same color scheme worn by Jack Cole's form-bending Plastic Man).

Attentive readers of The Squirrel Cage know the little gnome -- a doppleganger for the the Little Hitch-hiker (who also appears in the Foozland strips) -- is actually Paul Bunyan, the mythic logger giant from American tall tales!

|

| The Squirrel Cage by Gene Ahern - March 10, 1943 One of the earliest of the 'Paul Bunyan" strips - note the Little Hitch-hiker appears in the last panel |

This alone is a wonderful surreal gag, but Ahern dropped it after a couple of years. After Paul Bunyan tangles with an ill-tempered witch, he is reduced to a pint-sized lawn-ornament style gnome and banished to the mysterious country of Foozland, where the laws of humans and nature are radically different from our collective reality. After this transformation, the strip never again refers to the gnome as Paul Bunyan. He is essentially a cipher, with no name, no purpose, and no character -- the very opposite of the richly human Major Hoople and Judge Puffle.

The Bunyan-gnome initially wanders Foozland with a vague purpose of returning to his own world and form. This purpose becomes hazy, and finally forgotten as he is subsumed into the dreamworld of Foozland. Reading the Foozland strips in sequence reveals a "hidden" story of a character lost in a dream and unable to wake up.

Bunyan-gnome occasionally breaks through the borders of Foozland, but instead of returning to our universe, he finds himself in places like Goonia, which is merely another country in the un-named alternate universe. The strip is filled with a never-ending labyrinth of magic doors, caves, tunnels, and stairways that force the gnome (and the reader) to abandon all sense of direction and bearing. Ahern has created on paper a metaphor for what living itself feels like (at least living unconsciously), with its unexpected twists and turns that lead us through a daily parade of bewildering dead-ends in our search for security and reassuring (and non-existent) consistency.

The main visual symbol of travel in the Foozland strips is the ever-present Road, on which characters mostly travel left-to-right, in a mirror-image of the way English-speaking peoples read symbols and (most) sequential graphic narratives.

Minor masterpieces like The Squirrel Cage, because they have been ignored and forgotten, appear to spring up from nowhere, but this is far from the the truth. This lost comic strip actually continues a centuries-old tradition of allegorical storytelling, and traces to some surprising cultural cousins on the nut-laden screwball family tree.

The Origins of Foozland: Bunyan to Bunion

In considering the possible antecedents of Gene Ahern's Foozland, it helps to recognize the strip has an allegorical tone. In some cases, the strips may function as an allegory -- which is a story structure in which characters symbolize ideas and concepts -- and some cases, the strips only assume an allegorical tone, because at their heart, they are more surreal, eschewing any direct, one-to-one correlations between character and concept.This was, after all, first and foremost, entertainment for the masses.

The allegorical tone of Gene Ahern's Foozland strips can be traced back to A Pilgrim's Progress, a little-known series by Winsor McCay, one of the greatest artists of the medium.

|

| Perhaps the first great allegorical comic - A Pilgrim's Progress by Winsor McCay |

According to Allan Holtz's American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide (2012), A Pilgrim's Progress ran on weekdays from June 26, 1905 to May 4, 1909.

In McCay's A Pilgrim's Progress, we see a tall, gaunt man clad in black carrying a suitcase called "Dull Care." As with the gnome-Paul-Bunyan in The Squirrel Cage, he seems to almost always journey from left to right, on an eternal Road. McCay's Pilgrim (who is sometimes referred to as "Mr. Bunion", a play on John Bunyan's name) ) encounters one tortured soul after another, and is unable to put his suitcase down to help. In the example shown above, we see a man driven crazy by his own outrage at the world's injustices -- unable to see that his "truth-telling" is really a form of blindness. He's an allegorical figure representing mindless blaming. Other people our Pilgrim encounters represent greed, gluttony, lust, hypocrisy, and so on. The Pilgrim himself respresents Everyman, who is burdened with the weight of the world and "worries for the entire universe."

|

| A Pilgrim's Progress by Winsor McCay From Winsor McCay The Early Works Volume 2, page 174 (Checker) |

Signing his series as "Silas," McCay reminds me of Hank Williams posing as "Luke the Drifter" -- both men adopting a new persona to deliver sermons in the form of entertainment.

In his lilting musical sermon, "I've Been Down That Road Before," Hank Williams recites:

"To bully folks and play mean tricks was once my pride and joy

Till one day I was toted home and mama didn't know her little boy

'My head was swelled up so doggone big I couldn't get it through my front door

Now I ain't just talkin' to hear myself, cause I been down that road before"

The image of a man's head swollen so large seems oddly resonant with Winsor McCay's dream imagery, not to mention some scenes from the Foozland stories which explicitly feature swelled heads and other physical transformations. Compare William's "doggone big" head with McCay's giant hammer in the last panel of the Pilgrim's Progress example above.

Note also William's use of the allegory of the Road as spiritual path. This is the same road McCay's Pilgrim and Ahern's Paul Bunyan-gnome travel.

Williams adopted the alter-ego of Luke as a way to deliver sermons to 1950s America without lessening the marketability of his name, popularly associated with "honky tonk" country and western songs like "Your Cheatin' Heart."

You can here the entire Luke the Drifter sermon of "I've Been Down That Road Before," here:

The "Dull Care" suitcase Winsor McCay's pilgrim totes -- a burden he cannot share -- also resonates with another 20th century musical icon, the 1968 song The Weight. Composed and performed by The Band, and appearing as the centerpiece of their first album, Music From Big Pink, the song was inspired by Luis Bunuel's symbolic films of spiritual quests through absurd situations. The Weight seeks to create an allegory of a burdened man wandering, very much like McCay's Pilgrim and William's Luke the Drifter. The wanderer carries a "bag" (which in 1968 America had a double meaning, since "bag" was a slang for "purpose" -- as in "what's your bag, man?") and encounters a dizzying variety of odd characters.

"I picked up my bag, and went looking for a place to hide

When I saw old Carmen and the Devil, walkin' side by side

I said "Hey Carmen, let's go downtown."

She said, "I gotta go, but my friend can stick around."

- The Weight, The Band

One of the characters in The Weight is named Luke, perhaps a tip of the cowboy hat to Hank.

The actual full title of McCay's strip is A Pilgrim's Progress by Mr. Bunion. The readers of 1905-1909 would have been more familiar with the comical, self-depreciating reference to John Bunyan, author of the 17th century bestseller, A Pilgrim's Progess.

|

| John Bunyan - not a screwball artist, but pretty screwy |

Bunyan, who began writing Pilgrim's Progress while in prison for preaching without a license, would have fit right in with the strange characters of The Weight, McCay's worlds, and Foozland. He spent much of his adult life seeking to redeem his wild youth in which he committed such immoral acts as dancing and bell-ringing. He was -- to give him credit -- legendary among his young peers for his ability to swear like a sailor. Bunyan apparently turned his wordsmithing talent to a higher purpose, and wrote one of the most famous books in the English language, A Pilgrim's Progress, a book that perhaps the younger Bunyan might have said was damned good and fucking weird.

Here's a small part of the Wiki summary of the book:

"On his way to the Wicket Gate, Christian is diverted by Mr. Worldly Wiseman into seeking deliverance from his burden through the Law, supposedly with the help of a Mr. Legality and his son Civility in the village of Morality, rather than through Christ, allegorically by way of the Wicket Gate."We can go back further than John Bunyan and the 17th century, to Dante's early 14th century Divine Comedy, an exploration of Heaven, Hell and Purgatory, filled with surrealism and some of the best allegory money can buy. Modern day cartoonist-allegorist Gary Panter has recreated two of the books of The Divine Comedy, with Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo's Inferno (2006).

|

| Milt Gross' Count Screwloose witnesses widespread insanity in a spectacular panel from April 5, 1931 |

The witnessing of humanity's suffering and unconscious insanity that McCay's Pilgrim provides is not that different from the adventures of Milt Gross' Count Screwloose, who regularly escapes from the looney bin (sometimes with a Rube Goldberg machine) only to see so much craziness in the outside world that he is happy, at strip's end, to return to the relatively sane world of the Nuttycrest asylum for the mentally disturbed.

When you look at it, there seems to be some sort ongoing discussion, first in strange books and then in strange comics, about journeys through screwball worlds.

Can it be mere co-incidence that Ahern shifted his wacky screwball strip about two inventors and a little hitch-hiker into an allegory by way of a character called Bunyan? Perhaps the DNA of the secret history of screwball comics looks something like this:

When we consider the dreamlike imagery found in The Squirrel Cage (and The Nut Brothers, an earlier Ahern surreal romp) it makes sense, then to look at the first page of the first publication of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress and see the word "dream" write large:

|

| Title page for John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress |

The Fun of Going Nowhere

When he created the Foozland continuity in The Squirrel Cage, Ahern built a serial dream that lasted years and went nowhere. The very title of the strip is a natural extension of the many squirrel and nut labels used in screwball comics, from Rube Goldberg's Boob McNutt to Ahern's own Squirrel Food and Nut Brothers. But there's another layer to the strip's title, since a squirrel cage is a confining environment in which a squirrel can run forever without ever getting anyplace -- just like the Buyan-gnome in Foozland.

With his invention of Foozland in The Squirrel Cage, Gene Ahern built one of the most elegant and incisive tools for social commentary in all of American comics. The strip below, from 1945, the first year of the Foozland continuity (at some point, something must be said about the meaning of Foozland's birth coinciding with the end of World War 2 and the arrival of The Bomb), provides an allegory on leadership with some dreamlike lampoons of government and social responsibility.

|

| The Squirrel Cage by Gene Ahern - April 8, 1945 (from the collection of Paul C. Tumey) |

The impulsive King of Foozland encounters the Bunyan-gnome, who is always on The Road, and makes him King. The crowned gnome, now bowed to, has no idea how to be a King. He stands on a path that has mysteriously developed a set of steps leading down - an allegorical symbol that he may be headed for a moral descent if he doesn't use his newly acquired power well.

Next, the King must sign a law -- the lawmaker acknowledges the power of the crown, whil ealso acknowledging that the gnome is not the real King. The law itself is comically huge, a giant scroll that is

so heavy (the Weight) he struggles to carry it.

The law is against beards, but as the lawmaker explains this, a long full beard appears on his face.

In the early 1990s, I lived in Leominster, Massachusetts, a small town filled with plastic factories and -- ironically -- famous as the birthplace and home town of Johnny Appleseed. One day, while walking home through the city cemetery, I came across a curious gravestone:

It seems that in the late 18th century, Leominster citizen Joseph Palmer was intolerantly attacked by his fellow townsmen for wearing a full beard. The book, Weird New England, tells us his clean-shaven peers thought Palmer's full beard was "antisocial and sinful." This resonantes with John Bunyan's self-persecution for dancing and bell-ringing. He was jailed for causing a disturbance of the peace and kept for a year. Palmer was finally released, refusing to cut his well-groomed beard. His jailers tied him to a chair and threw him from the jail. The "no-beard" law in Gene Ahern's April 8, 1945 Squirrel Cage reminds me of Palmer. In effect, when the beard magically appears on the man who wants to outlaw beards, something is being said about human versus moral law. Realizing he has a beard (without ever questioning why or how that he could grow a long beard in a second), the lawmaker instant shifts his focus to outlawing people WITHOUT a beard -- thus he has become an allegorical figure for Intolerance. In the background a Herriman-esque tree appears to have a fuzzy hat, or perhaps a beard.

Realizing that he almost signed into law something that "put people in trouble," the gnome begins to question whether it is right for him to wear the crown. There's an old saying that the best leaders are those that do not wish to lead -- it seems the gnome has common sense, and perhaps even moral sense. The tree he touches is multi-colored and oddly shaped -- it seems to resonate with a meaning, but its unclear what that meaning may be.

In a small heroic gesture, the gnome divests himself of the power and responsibility of rulership, and bestows it upon a scarecrow -- a "fake" human.

In the last panel, the former King of Foozeland, now a mere subject, bows to the crowned scarecrow. It's almost as if there's no importance placed on who leads, but only that thereis a leader -- even if it's only a scarecrow. Woody Guthrie once famously said, when asked of about his political affiliation, "right wing, left wing, chicken wing -- it's all the same to me." Of course, this was nonsense, since Guthrie was a well-known radical activist of his time, but in this nonsense -- like the nonsense of The Squirrel Cage -- is valuable -- and shocking -- wisdom.

Your Screwball Scribe,

Paul Tumey

All text copright 2012 Paul C. Tumey

↧

Some Winsor McCay Pilgrims for Thanksgiving

I'm thankful for comics. Even at age 50, I still discover comics I never heard of before that I can feel excited about. It helps to make my own DULL CARE valise seem lighter and bearable. I find my love for comics and their rich history is stronger than ever.

My latest discovery is Winsor McCay's A Pilgrim's Progress by Mister Bunion. So, for Thanksgiving 2012, I'll appropriately share with you a selection of my favorite Pilgrims.

McCay, famous for his Little Nemo In Slumberland comics (which ran concurrently with his Pilgrim series), was incredibly hard-working and productive. As such, there are hundreds, if not thousands of fascinating, lesser-known comics by this master (dare we say genius?) of the form to discover. Of these, A Pilgrim's Progress (which McCay signed with the pen name Silas, apparently for contractual reasons) is certainly one of the strangest -- and, in my opinion, one of the most wonderfully screwy comic strip series ever done.

According to Allan Holtz's American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide (University of Michigan Press, 2012), A Pilgrim's Progress by Mister Bunion was entirely written and drawn by Winsor McCay and ran on weekdays in the New York Evening Telegram from June 26 1905 to May 4, 1909, with a 4 month hiatus in early 1906.

As I discussed in my previous post, McCay's strip was inspired by the 17th century allegorical novel, A Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan. Like Bunyan, McCay is interested in exploring the human condition (and in some strips, the canine condition, and others). In a bizarre and entertaining way, these strips are filled with wisdom about how life seems to work for most of us.

The strip's anti-hero, Mister Bunion, is aptly named, for he seems to be forever walking through cities, countrysides, American landmarks, shops, theaters, and just about anywhere you can imagine. Bunion is tall, thin, dressed in a solid black suit, and wears an impossibly high stovepipe hat. McCay used a short, fat version of this character design for Dr. Pill in Little Nemo.

Like Dr. Pill, Mr. Bunion carries a valise. His valise is (usually) labeled DULL CARE, and it is his burden in life to carry it. Several of the episodes are built around Mr. Bunion's attempts to rid himself of the accursed suitcase. These attempts, of course, never work. In one example, he hurls it into the Grand Canyon. In the strip below, he climbs to the top of the Washington Monument, hoping the fall from such a height might destroy the valise and free him.

I love that silent last panel. In some of the strips, Bunion seeks Glad Avenue in a continual futile but fascinating search that would be echoed generations later in the Foozland strips of Gene Ahern's The Squirrel Cage, in which the anti-hero seeks escape from an alternate universe. It may only be co-incidence that Ahern's character is also named Bunyan -- Paul Bunyan, the mythical lumberjack. In the next example, Bunion is walking down Rocky Road, seeking Glad Avenue. In the process, he finds some relief from his burden, but it only temporary.

McCay's forgotten comic resonates with a notable episode from the early Julius Knipl strips by a similar-minded comics creator, Ben Katchor. Consider this strip in which photographer Mr. Knipl finds a place to relieve himself of his "negatives" for perpetuity (or, say, 30 years), reprinted in the great 1991 collection, Cheap Novelties (I highly recommend this book).

The Buddha taught we create our own suffering through desire. Buddhism teaches us that it is our reaction to something that makes us happy or unhappy. In other words, there is nothing outside of us that can actually create happiness or unhappiness. There is an essential truth to this, I think -- and I find it useful. However, if I were in a Nazi concentration camp in WWII, I seriously doubt that I would be able to find a way to not suffer and make my reaction peaceful -- although perhaps some did. In any case, McCay's strip, not Buddhist, but also not explicitly Christian, is concerned with the suffering of a mundane life and how to escape it. In the strip below, Mr. Bunion, inspired by spiritual advice, decides to see his valise in a new light.

Of course, it's no use. In McCay's Pilgrim's Progress, life seems to inevitably cycle through its ups and downs, not matter how strong our resolve to remain in the light. A pilgrim is a person who journeys to a place for religious reasons. Mr. Bunion -- like many of us -- seems to be on an involuntary journey towards an unspecified sacred place. As with any great epic journey story, many different fellow travelers are met along the way. Most of the people Bunion meets are afflicted with some form of spiritual or moral illness. In most cases, they are unaware of their illness, and the strips assume even greater depth as we move the allegory of the literal Dull Care suitcase to the hidden faults of people. In the next example I'd like to share with you, Mr. Bunion encounters "the man with the changeable face," a man who is unable to help another for fear of losing what he has got -- and a totally oblivious hypocrite.

The man that Mr. Bunion meets in the above comic thinks of himself as a good person who is sincerely interested in the affairs of others, but in reality, he's fearful, grasping, and selfish. In the above comic, I am also extremely fascinated by the very tall and narrow chapeau Mr. Bunion dons.

In his Progress towards spiritual growth, Mr. Bunion also encounters animals. In the brilliant strip below, Bunion learns that not even a dog is free from suffering.